Circles in Architecture

Architects can use the strength of the circle while manipulating its appearance. The circle is the strongest 2-dimensional shape, so is the use of semicircular arches in architecture. Semicircles are often also found in the designs of amphitheaters

Some of today’s buildings are bewildering in their technological innovations. From Frank Gehry’s undulating façades to Zaha Hadid’s swooping structures, modern engineering has allowed architecture to transcend tradition. Complex structures and gestures aside, there’s something to be said about the elegance of bold, basic geometry.

After all, the Ancient Greeks built entire empires on the principles of geometry and proportion of basic shapes such as the triangle. This chronological collection of projects charts the recent history of circles in architecture, exploring how the shape can lend projects their identity, add an element of surprise or play a role in a larger system of strong geometries.

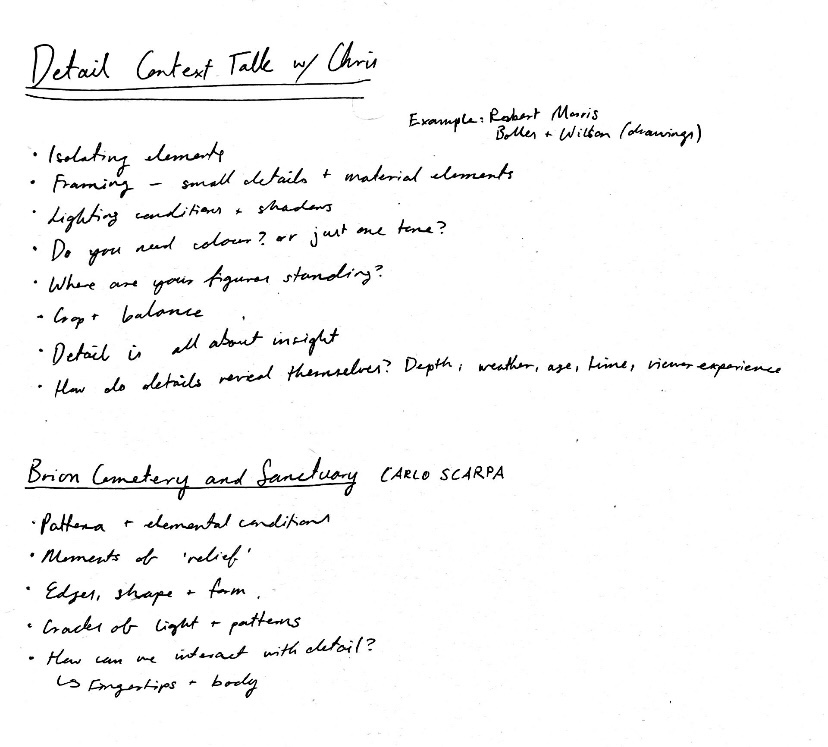

Carlo Scarpa

Italian architect Carlo Scarpa (1906–1978), is best known for his instinctive approach to materials, combining time-honored crafts with modern manufacturing processes and his intuitive ability for reimagining museums and public spaces. Through his seminal works, he has redefined ‘preservation,’ ‘conservation,’ ‘restoration,’ ‘renovation,’ ‘intervention’ and ‘reconstitution.’ Scarpa’s hyper intensive use of simple devices or ideas to create art stems from his influences of Venetian tradition and Japanese sensibilities.

Brion Cemetery and Sanctuary

I was particularly fascinated by this project by the Scarpa. He began designing this addition to an existing municipal cemetery in 1968. Although he continued to consider changes to the project, it was completed before his accidental death in 1978. The enclosure is a private burial ground for the Brion family, commissioned by Onorina Tomasi Brion, widow of the Brionvega company’s founder.

” I would like to explain the Brion Cemetery… I consider this work, if you permit me, to be rather good and which will get better over time. I have tried to put some poetic imagination into it, though not in order to create poetic architecture but to make a certain kind of architecture that could emanate a sense of formal poetry….The place for the dead is a garden….I wanted to show some ways in which you could approach death in a social and civic way; and further what meaning there was in death, in the ephemerality of life – other than these shoe-boxes.

This place of death is little like a garden. Incidentally, the great American cemeteries of the nineteenth century, in Chicago, for example, are extensive parks. No Napoleonic tomb, no! You can drive in with your car. There are beautiful monuments, for instance, those by Louis Henry Sullivan. Cemeteries now have become mere piled-up shoe boxes, one on top of the other. I wanted to express the naturalness of water and meadow, of water and earth. Water is the source of life.“

– Carlo Scarpa

This project fascinated me particularly because of the elements Scarpa layers to create such intricate details which evolves and weathers or grows over time. The materials and shapes, patterns and geometry he has crafted to create this masterpiece of architecture puts a lasting impression of me. This space appears to be a sacred site rich with history and culture. I find it beautiful how he places death in a garden in a civic context which showcases the meaning there is in both death and the ‘ephemerality’. this project definitely has me questioning whether I can take my project with a different visual and material approach which forms with nature and the urban site better.

Ephemerality – the concept of things being transitory, existing only briefly. Typically the term ephemeral is used to describe objects found in nature, although it can describe a wide range of things.

Looking into Websites and Projects for Spatial Designers

.

Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum // Studio Zhu Pei

Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum is located in the center of Jingdezhen historic district, adjacent to the Ming and Qing imperial kiln ruins. It is a national museum with special significance and a key project of Jiangxi Province. Main functions include: permanent exhibition, exchange exhibition, auditorium, amphitheater, multi-function hall, bookstore/souvenir shop, tea/cafe, restoration room, administrative office, storage, loading dock, and etc. The museum comprises more than half a dozen vaults based on the traditional form of the kilns. On the lower level, indoor and outdoor spaces are inter connected.

The Imperial Kiln Museum is not only deeply rooted in the specific natural, historical and cultural environment of Jingdezhen, but also injects new vitality and international influence into the old city. The Imperial Kiln Museum will build the revival of Jingdezhen’s traditional historical district together with the ruins of Imperial Kiln Factory, the scattered ruins of traditional folk kilns, the historical heritage of traditional dwellings and alleys.

Bronte Studio – SAHA design

Ceramicist Kati Watson engaged SAHA to design the smallest studio possible at the bottom of her garden. She has lived in the same Bronte house for the last 30 years, and wanted a space that would respect the landscape. A dream creative collaboration! The result is this beautiful, semi-open studio shelter where Kati can sit and pot with the terrain in full view.

Kati and Shaun have lived in their Bronte home for many years. A verdant garden weaves its way around the site, shielding the existing dwelling from view and casting long afternoon shadows. By raising a garden bed up as a green roof, Kati’s new ceramics studio disappears under coastal rosemary and grevilleas. Raw materials reflect the garden setting and a circular window, displaying Kati’s work, greets visitors as they arrive.

Built by Brad Swanson and photographed by Saskia Wilson.

https://www.saha.sydney/#project-redfern-studio

Louis Kahn

Regarded as one of the great master builders of the 20th Century, Louis Kahn (1901-1974) was one of America’s most influential modernist architects. With complex spatial compositions and a choreographic mastery of light, Kahn created buildings of archaic beauty and powerful universal symbolism. His uniqueness lies in his synthesis of the major conceptual traditions of modern architecture, from the École des Beaux-Arts and the constructive rationalism of the 19th Century to the Arts and Crafts movement and Bauhaus modernism, enhanced by the consideration of indigenous, non-western building traditions.

Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka, Bangladesh

The Capitol Complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh, fuses imposing grandeur with disarming simplicity, foreshadowing Postmodernism

Louis Kahn’s Capitol Complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh, is an epic work in the annals of modern architecture that is still shrouded in mystery. Dhaka was a critical site of Kahn’s new overtures in the Modernist cosmos. Located at the geographical and ideological edge of that cosmos, the project literally expanded the horizon of modern architecture, which was stagnating in its own ideological doldrums. In amalgamating a primordial intensity with a modern programme, and resuscitating the eroded civic purpose of architecture, Kahn was able to articulate in Dhaka a kind of mystical Modernism (which some would describe as a precursor to Postmodernism).

The significance of the Capitol Complex is inextricably linked with the national and political movement of the Bengalis. It is this correspondence between architectural form and cultural norms, often working at surreptitious levels, that has not been fully investigated. How much Kahn himself participated in these matters is not clear but it is possible that Kahn’s contemplation on architecture, ‘institution’ and landscape found in Dhaka a coincidental as well as reciprocal meaningfulness.

‘In allowing nature to invade an artefact, erode its envelope, make it porous, and finally repossess it, Kahn made the dynamics of weathering and landscaping visible’